The heat of Nebraska summer is subsiding, at least for the week. I know it will probably return, but I’m enjoying this sudden slide toward fall—a cold day, rain off and on, the ground littered with wet, brown leaves.

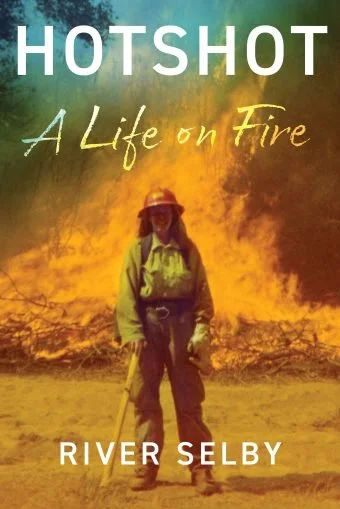

This season of my life has been busier than most. These days, I don’t get to read quite as many books as usual, but when I do, I savor it. Case in point: back in July, when my early copy of River Selby’s debut memoir Hotshot came in the mail, I parked my butt on the couch for an entire Saturday, devouring the book in one day. River is a close friend, and the experience of reading a beloved’s book never gets old: a mixture of love, awe, and admiration.

Last week, River visited Lincoln, speaking to a couple of classes at UNL and reading at our local independent bookstore, Francie & Finch. It was a lovely event, with River reading from the Nebraska chapter of Hotshot. Here’s a favorite bit of mine from that chapter (which is titled “Grasslands”):

In Nebraska my squad looped hose line around a house and a yellowing field dotted with giant cylinders of hay. After that we burned for days. Days and days. I recall yellow grass. Loose dirt. Homeowners bringing us cold drinks. Long dirt roads and the crickets, mice, and shrews who fled across them, towards safety. (Hotshot, 225)

Yes, I remember thinking—that’s Nebraska. Afterwards, River and I went back and forth for a short conversation before taking questions from the audience. We talked about their relationship to place and how it serves as an organizing element of the book, the way they vividly describe the physical labor of wildland firefighting, and how their practices of observation and research transformed as they wrote the book.

Hotshot is an ambitious book, and one that accomplished much in its pages; it’s a carefully researched history of fire suppression policy, colonization, and climate change, as well as a vivid personal narrative exploring identity, gender, trauma, and connection, among other things. It is also—in my eye—a book that lingers beautifully in moments of image and poetry.

When I took my copy of Hotshot from its place in a windowsill stack to write these notes, a bug slithered out of it: a small silverfish. I squealed a bit, then laughed, delighted at the poetic image of this little bit of nature literally crawling out of the book. It felt fitting—like the insect had crawled right out of one of River’s descriptions, becoming a tangible, slippery thing. And images, after all, are the things I keep returning to when I open the book and flip through the pages—images like the landscape of the Viveash fire in New Mexico in 2000, which River describes as “bare as a moonscape” in some places. Or the “sharp-spined hills draped with mint green sage” as they drove north of the Wyoming flatlands. Or this description of a fire in Southern California, which comes early in the book:

A strong gust of wind coaxed my fire towards Gunnar’s. The wind paused and the fire stopped short, momentarily righting itself before another gust blew it into Gunnar’s fire, like a strong exhale. For all the years I worked in fire, I would observe this rhythm, so much like my own breathing. The fire was seeking oxygen. It seemed to breathe like any other animal, popping, whistling, crackling, and sighing. (Hotshot, 52)

I could go on listing moments of gorgeous language—the book is packed with them. Instead, I’ll simply encourage you to get yourself a copy and read it. You can order a copy on Bookshop, or through your local independent bookstore, or wherever you buy books (or request it from the library!). The audiobook is also now available.

Further Reading: